A small US city experiments with AI to find out what residents want

Bowling Green, Kentucky, is home to 75,000 residents who recently wrapped up an experiment in using AI for democracy: Can an online polling platform, powered by machine learning, capture what residents want to see happen in their city? When Doug Gorman, elected leader of the county that includes Bowling Green, took office in 2023, it…

Bowling Green, Kentucky, is home to 75,000 residents who recently wrapped up an experiment in using AI for democracy: Can an online polling platform, powered by machine learning, capture what residents want to see happen in their city?

When Doug Gorman, elected leader of the county that includes Bowling Green, took office in 2023, it was the fastest-growing city in the state and projected to double in size by 2050, but it lacked a plan for how that growth would unfold. Gorman had a meeting with Sam Ford, a local consultant who had worked with the surveying platform Pol.is, which uses machine learning to gather opinions from large groups of people and identify topics they agree on.

They “needed a vision” for the anticipated growth, Ford says. The two convened a group of volunteers with experience in eight areas: economic development, talent, housing, public health, quality of life, tourism, storytelling, and infrastructure. They built a plan to use Pol.is to help write a 25-year plan for the city. The platform is just one of several new technologies used in Europe and increasingly in the US to help make sure that local governance is informed by public opinion.

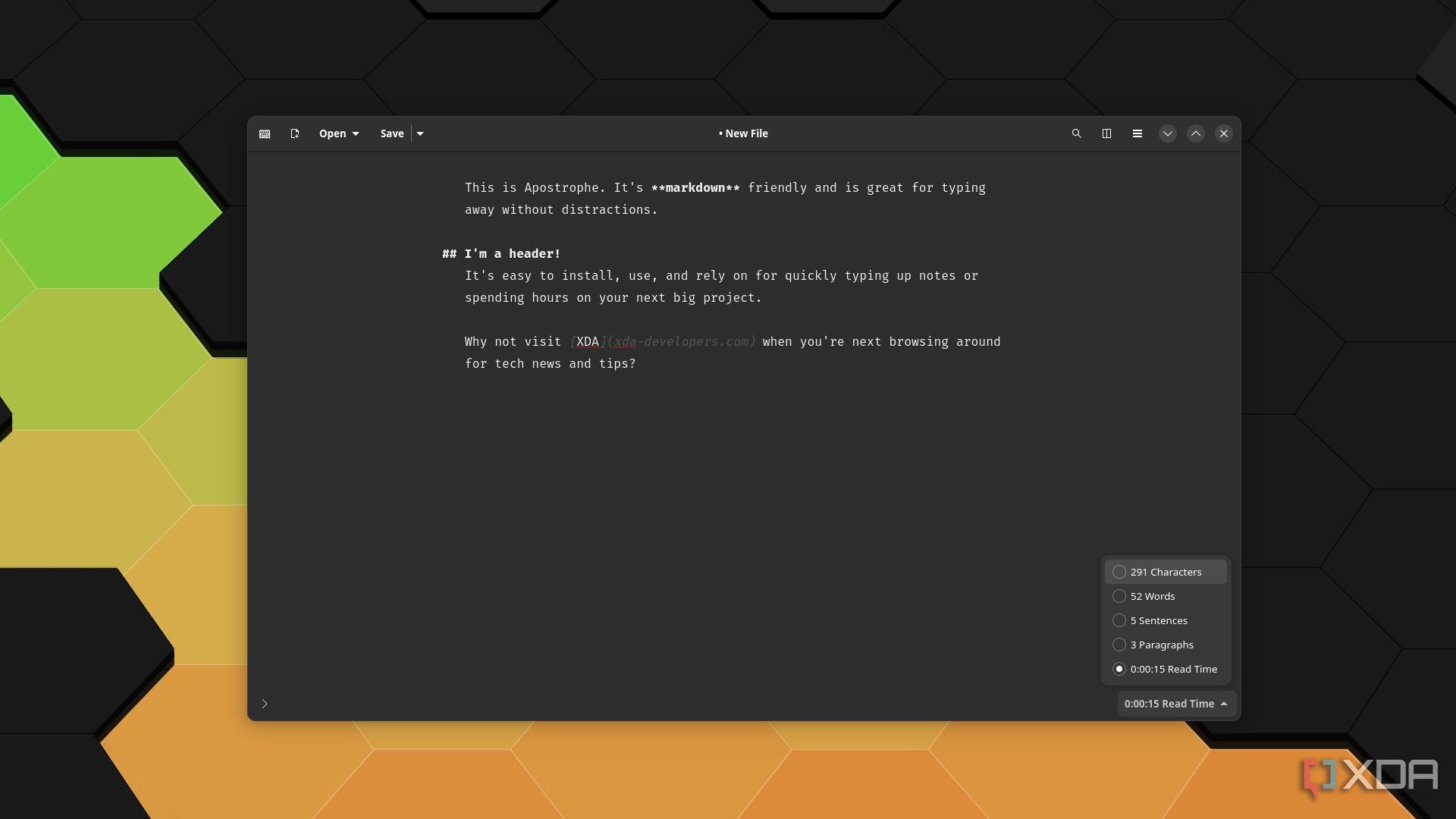

After a month of advertising, the Pol.is portal launched in February. Residents could go to the website and anonymously submit an idea (in less than 140 characters) for what the 25-year plan should include. They could also vote on whether they agreed or disagreed with other ideas. The tool could be translated into a participant’s preferred language, and human moderators worked to make sure the traffic was coming from the Bowling Green area.

Over the month that it was live, 7,890 residents participated, and 2,000 people submitted their own ideas. An AI-powered tool from Google Jigsaw then analyzed the data to find what people agreed and disagreed on.

Experts on democracy technologies who were not involved in the project say this level of participation—about 10% of the city’s residents—was impressive.

“That is a lot,” says Archon Fung, director of the Ash Center for Innovation and Democratic Governance at the Harvard Kennedy School. A local election might see a 25% turnout, he says, and that requires nothing more than filling out a ballot.

“Here, it’s a more demanding kind of participation, right? You’re actually voting on or considering some substantive things, and 2,000 people are contributing ideas,” he says. “So I think that’s a lot of people who are engaged.”

The plans that received the most attention in the Bowling Green experiment were hyperlocal. The ideas with the broadest support were increasing the number of local health-care specialists so residents wouldn’t have to travel to nearby Nashville for medical care, enticing more restaurants and grocery stores to open on the city’s north side, and preserving historic buildings.

More contentious ideas included approving recreational marijuana, adding sexual orientation and gender identity to the city’s nondiscrimination clause, and providing more options for private education. Out of 3,940 unique ideas, 2,370 received more than 80% agreement, including initiatives like investing in stormwater infrastructure and expanding local opportunities for children and adults with autism.

The volunteers running the experiment were not completely hands-off. Submitted ideas were screened according to a moderation policy, and redundant ideas were not posted. Ford says that 51% of ideas were published, and 31% were deemed redundant. About 6% of ideas were not posted because they were either completely off-topic or contained a personal attack.

But some researchers who study the technologies that can make democracy more effective question whether soliciting input in this manner is a reliable way to understand what a community wants.

One problem is self-selection—for example, certain kinds of people tend to show up to in-person forums like town halls. Research shows that seniors, homeowners, and people with high levels of education are the most likely to attend, Fung says. It’s possible that similar dynamics are at play among the residents of Bowling Green who decided to participate in the project.

“Self-selection is not an adequate way to represent the opinions of a public,” says James Fishkin, a political scientist at Stanford who’s known for developing a process he calls deliberative polling, in which a representative sample of a population’s residents are brought together for a weekend, paid about $300 each for their participation, and asked to deliberate in small groups. Other methods, used in some European governments, use jury-style groups of residents to make public policy decisions.

What’s clear to everyone who studies the effectiveness of these tools is that they promise to move a city in a more democratic direction, but we won’t know if Bowling Green’s experiment worked until residents see what the city does with the ideas that they raised.

“You can’t make policy based on a tweet,” says Beth Simone Noveck, who directs a lab that studies democracy and technology at Northeastern University. As she points out, residents were voting on 140-character ideas, and those now need to be formed into real policies.

“What comes next,” she says, “is the conversation between the city and residents to develop a short proposal into something that can actually be implemented.” For residents to trust that their voice actually matters, the city must be clear on why it’s implementing some ideas and not others.

For now, the organizers have made the results public, and they will make recommendations to the Warren County leadership later this year.