Europe is finally getting serious about commercial rockets

Europe is on the cusp of a new dawn in commercial space technology. As global political tensions intensify and relationships with the US become increasingly strained, several European companies are now planning to conduct their own launches in an attempt to reduce the continent’s reliance on American rockets. In the coming days, Isar Aerospace, a…

Europe is on the cusp of a new dawn in commercial space technology. As global political tensions intensify and relationships with the US become increasingly strained, several European companies are now planning to conduct their own launches in an attempt to reduce the continent’s reliance on American rockets.

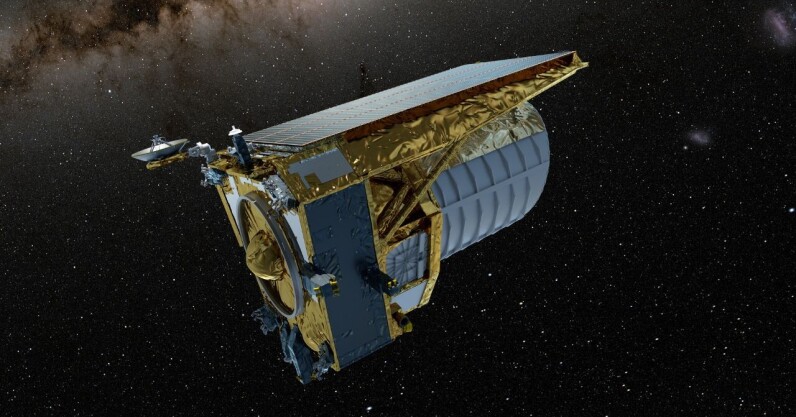

In the coming days, Isar Aerospace, a company based in Munich, will try to launch its Spectrum rocket from a site in the frozen reaches of Andøya island in Norway. A spaceport has been built there to support small commercial rockets, and Spectrum is the first to make an attempt.

“It’s a big milestone,” says Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer and spaceflight expert at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Massachusetts. “It’s long past time for Europe to have a proper commercial launch industry.”

Spectrum stands 28 meters (92 feet) tall, the length of a basketball court. The rocket has two stages, or parts, the first with nine engines—powered by an unusual fuel combination of liquid oxygen and propane not seen on other rockets before, which Isar says results in higher performance—and the second with a single engine to give satellites their final kick into orbit.

The ultimate goal for Spectrum is to carry satellites weighing up to 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds) to low Earth orbit. On this first launch, however, there are no satellites on board, because success is anything but guaranteed. “It’s unlikely to make it to orbit,” says Malcolm Macdonald, an expert in space technology at Strathclyde University in Scotland. “The first launch of any rocket tends not to work.”

Regardless of whether it succeeds or fails, the launch attempt heralds an important moment as Europe tries to kick-start its own private rocket industry. Two other companies—Orbex of the UK and Rocket Factory Augsburg (RFA) of Germany—are expected to make launch attempts later this year. These efforts could give Europe multiple ways to reach space without having to rely on US rockets.

“Europe has to be prepared for a more uncertain future,” says Macdonald. “The uncertainty of what will happen over the next four years with the current US administration amplifies the situation for European launch companies.”

Trailing in the US’s wake

Europe has for years trailed behind the US in commercial space efforts. The successful launch of SpaceX’s first rocket, the Falcon 1, in 2008 began a period of American dominance of the global launch market. In 2024, 145 of 263 global launch attempts were made by US entities—and SpaceX accounted for 138 of those. “SpaceX is the benchmark at the moment,” says Jonas Kellner, head of marketing, communications, and political affairs at RFA. Other US companies, like Rocket Lab (which launches from both the US and New Zealand), have also become successful, while commercial rockets are ramping up in China, too.

Europe has launched its own government-funded Ariane and Vega rockets for decades from the Guiana Space Centre, a spaceport it operates in French Guiana in South America. Most recently, on March 6, the European Space Agency (ESA) launched its new heavy-lift Ariane 6 rocket from there for the first time. However, the history of rocket launches from Europe itself is much more limited. In 1997 the US defense contractor Northrop Grumman air-launched a Pegasus rocket from a plane that took off from the Canary Islands. In 2023 the US company Virgin Orbit failed to reach orbit with its LauncherOne rocket after a launch attempt from Cornwall in the UK. No vertical orbital rocket launch has ever been attempted from Western Europe.

Isar Aerospace is one of a handful of companies hoping to change that with help from agencies like ESA, which has provided funding to rocket launch companies through its Boost program since 2019. In 2024 it awarded €44.22 million ($48 million) to Isar, Orbex, RFA, and the German launch company HyImpulse. The hope is that one or more of the companies will soon begin regular launches from Europe from two potential sites: Isar’s chosen location in Andøya and the SaxaVord Spaceport on the Shetland Islands north of the UK, where RFA and Orbex plan to make their attempts.

“I expect four or five companies to get to the point of launching, and then over a period of years reliability and launch cadence [or frequency] will determine which one or two of them survives,” says McDowell.

Unique advantages

In their initial form these rockets will not rival anything on offer from SpaceX in terms of size and cadence. SpaceX sometimes launches its 70-meter (230-foot) Falcon 9 rocket multiple times per week and is developing its much larger Starship vehicle for missions to the moon and Mars. However, the smaller European rockets can allow companies in Europe to launch satellites to orbit without having to travel all the way across the Atlantic. “There is an advantage to having it closer,” says Kellner, who says it will take RFA one or two days by sea to get its rockets to SaxaVord, versus one or two weeks to travel across the Atlantic.

Launching from Europe is useful, too, for reaching specific orbits. Traditionally, a lot of satellite launches have taken place near the equator, in places such as Cape Canaveral in Florida, to get an extra boost from Earth’s rotation. Crewed spacecraft have also launched from these locations to reach space stations in equatorial orbit around Earth and the moon. From Europe, though, satellites can launch north over uninhabited stretches of water to reach polar orbit, which can allow imaging satellites to see the entirety of Earth rotate underneath them.

Increasingly, says McDowell, companies want to place satellites into sun-synchronous orbit, a type of polar orbit where a satellite orbiting Earth stays in perpetual sunlight. This is useful for solar-powered vehicles. “By far the bulk of the commercial market now is sun-synchronous polar orbit,” says McDowell. “So having a high-latitude launch site that has good transport links with customers in Europe does make a difference.”

Europe’s end goal

In the longer term, Europe’s rocket ambitions might grow to vehicles that are more of a match for the Falcon 9 through initiatives like ESA’s European Launcher Challenge, which will award contracts later this year. “We are hoping to develop [a larger vehicle] in the European Launcher Challenge,” says Kellner. Perhaps Europe might even consider launching humans into space one day on larger rockets, says Thilo Kranz, ESA’s program manager for commercial space transportation. “We are looking into this,” he says. “If a commercial operator comes forward with a smart way of approaching [crewed] access to space, that would be a favorable development for Europe.”

A separate ESA project called Themis, meanwhile, is developing technologies to reuse rockets. This was the key innovation of SpaceX’s Falcon 9, allowing the company to dramatically drive down launch costs. Some European companies, like MaiaSpace and RFA, are also investigating reusability. The latter is planning to use parachutes to bring the first stage of its rocket back to a landing in the sea, where it can be recovered.

“As soon as you get up to something like a Falcon 9 competitor, I think it’s clear now that reusability is crucial,” says McDowell. “They’re not going to be economically competitive without reusability.”

The end goal for Europe is to have a sovereign rocket industry that reduces its reliance on the US. “Where we are in the broader geopolitical situation probably makes this a bigger point than it might have been six months ago,” says Macdonald.

The continent has already shown it can diversify from the US in other ways. Europe now operates its own successful satellite-based alternative to the US Global Positioning System (GPS), called Galileo; it began launching in 2011 and is four times more accurate than its American counterpart. Isar Aerospace, and the companies that follow, might be the first sign that commercial European rockets can break from America in a similar way.

“We need to secure access to space,” says Kranz, “and the more options we have in launching into space, the higher the flexibility.”

![Mobile Legends: Bang Bang [MLBB] Free Redeem Codes March 2025](https://www.talkandroid.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Screenshot_20240704-093036_Mobile-Legends-Bang-Bang.jpg)