Study turns up new clues, new questions in the search for the roots of consciousness

Seven years after they started, neuroscientists have published the results of a landmark study that was designed to determine which theory of human consciousness came closest to the mark — and those results are decidedly mixed. The bad news is that neither of the leading theories held a clear advantage in explaining how consciousness arises. The good news is that researchers picked up new clues about where to look. One of the leaders of the effort — Christof Koch, a meritorious investigator at the Seattle-based Allen Institute — said he was heartened by the state of the debate. “Adversarial collaboration… Read More

Seven years after they started, neuroscientists have published the results of a landmark study that was designed to determine which theory of human consciousness came closest to the mark — and those results are decidedly mixed.

The bad news is that neither of the leading theories held a clear advantage in explaining how consciousness arises. The good news is that researchers picked up new clues about where to look.

One of the leaders of the effort — Christof Koch, a meritorious investigator at the Seattle-based Allen Institute — said he was heartened by the state of the debate.

“Adversarial collaboration fits within the Allen Institute’s mission of team science, open science and big science, in service of one of the biggest, and most long-standing, intellectual challenges of humanity: the Mind-Body Problem,” Koch said today in a news release. “Unraveling this mystery is the passion of my entire life.”

The history of the study that was published today in the journal Nature goes back to a workshop that took place at the Allen Institute in 2018. The discussion focused on two different hypotheses about the nature of consciousness.

One hypothesis, known as Integrated Information Theory or IIT, holds that consciousness arises through the interaction and cooperation of various parts of the brain as information is processed.

“IIT suggests that consciousness emerges when information inside a system (like the brain) is highly connected and unified; and as long as the information remains unified, it will be consciously perceived,” Koch, who has been a proponent of IIT, told GeekWire in an email. “IIT starts with consciousness and then infers the causal property any mechanism, such as a brain, needs to obey to be conscious.”

The other leading hypothesis is called Global Neuronal Workspace Theory. “GNWT suggests a network of brain areas spotlight important pieces of information in the brain — bringing it to the forefront of our minds — broadcasting it widely the moment it enters consciousness, and this produces conscious experience,” Koch said. “GNWT starts with psychology and neuroscience, and seeks to distill consciousness from these.”

Was it possible to find evidence favoring one hypothesis or the other? In 2019, Koch and other researchers worked out a series of tests that they thought could address the issue. The Cogitate Consortium recruited 256 human subjects across 12 laboratories to have their brain activity recorded.

The research team monitored the brain’s blood flow, electrical activity and magnetic resonance readings while the experimental subjects interacted with a series of on-screen images of faces, objects, letters and symbols. All those data points were analyzed to track how impulses moved between regions of the brain.

If the neural nexus of consciousness could be traced to the prefrontal cortex, that would favor the GNWT hypothesis. But if the brain activity associated with consciousness was centered toward the back of the brain, in the posterior cortex, that would argue against GNWT — and in favor of IIT.

“Here the evidence is decidedly in favor of the posterior cortex,” Koch said. “Either information pertaining to the conscious experience couldn’t be found in the front, or it was far weaker than in the back. This supports the idea that while the frontal lobes are critical to intelligence, judgment, reasoning, etc., they are not critically involved in seeing, in conscious visual perception.”

The results of the experiment also suggested the brain activity that’s correlated with consciousness continued as long as a conscious experience was sustained. That was another strike against GNWT, which predicts that such activity should peak at the beginning and end of an experience, but fall off in the middle.

In a third experimental faceoff, however, GNWT had the upper hand: The researchers found that there was a high-frequency oscillation between the brain’s early visual cortical regions and the front of the brain — but not between those early visual regions and the back of the brain, as predicted by the IIT hypothesis.

The Cogitate Consortium provided a progress report on the experiment in 2023, acknowledging that there wasn’t a clear winner but pledging to continue the study. That lack of a clear result caused Koch to lose a decades-old bet with a philosopher, which he paid off with a case of fine wine.

In this week’s Nature research paper, the consortium’s scientists acknowledged that they still haven’t settled on a winner. Nevertheless, they gleaned useful information about the regions of the brain that appear to be associated with consciousness.

“We found information about conscious content in visual, ventrotemporal and inferior frontal cortex, with sustained responses in occipital and lateral temporal cortex reflecting stimulus duration, and content-specific synchronization between frontal and early visual areas,” the researchers reported.

Koch said there are plenty of reasons for continuing to delve into one of life’s deepest mysteries.

“If we want to understand the substrate of consciousness, who has it (adults, pre-linguistic children, a second trimester fetus, a dog, a mouse, a squid, a raven, a fly, etc.) we need to identify the underlying mechanisms in the brain, both for conceptual reasons (why these and not other ones) as well as for clinical ones,” he said in his email.

Being able to determine the state of mind of an unresponsive patient could make a critical difference when it comes to deciding whether or not to withdraw life-sustaining treatment. Some studies have suggested that more than half of the deaths that take place in critical care occur following withdrawal of treatment. But Koch cited a study reporting that around a quarter of unresponsive patients are actually conscious but “unable to signal this at the bedside.”

Koch is one of the founders of Intrinsic Powers, a venture that is working on a medical device that could serve as a “consciousness-meter” for unresponsive patients. The device uses trans-cranial magnetic stimulation to stimulate the brain, and then checks for a response. “Whether or not IIT is the correct theory of consciousness, the device works as intended,” Koch said.

Even though the results of the years-long experiment in adversarial collaboration turned out to be inconclusive, Koch hasn’t given up on IIT. “The challenge is to come up with ways to explain the null result in the third prediction,” he said. “We’re working on that.”

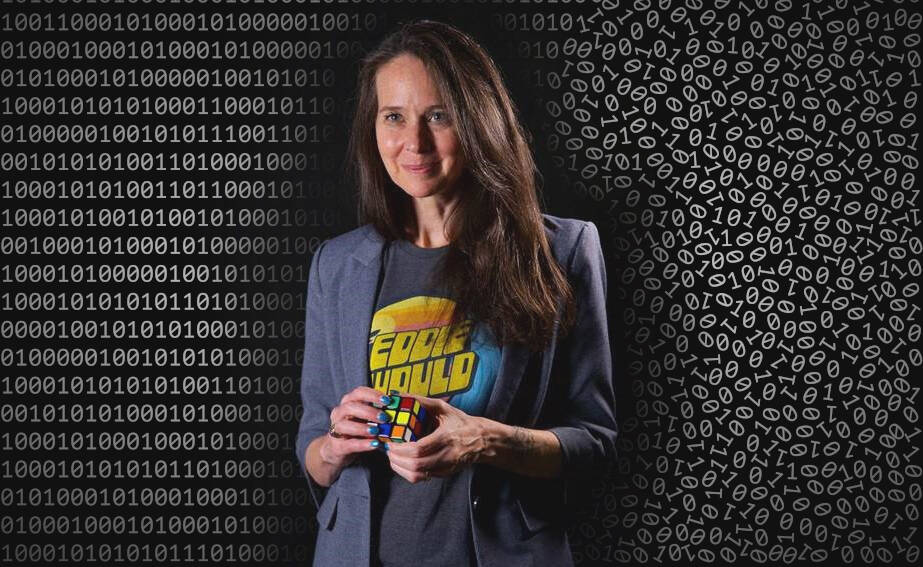

Koch is among more than 40 authors of the Cogitate Consortium study in Nature, titled “Adversarial Testing of Global Neuronal Workspace and Integrated Information Theories of Consciousness.” The study’s corresponding author is Lucia Melloni of the New York University Grossman School of Medicine.

-xl.jpg)

![[Free Webinar] Guide to Securing Your Entire Identity Lifecycle Against AI-Powered Threats](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjqbZf4bsDp6ei3fmQ8swm7GB5XoRrhZSFE7ZNhRLFO49KlmdgpIDCZWMSv7rydpEShIrNb9crnH5p6mFZbURzO5HC9I4RlzJazBBw5aHOTmI38sqiZIWPldRqut4bTgegipjOk5VgktVOwCKF_ncLeBX-pMTO_GMVMfbzZbf8eAj21V04y_NiOaSApGkM/s1600/webinar-play.jpg?#)