A Canadian mining company wants Trump’s permission to mine the deep sea

The Metals Company, which has been trying for years to exploit battery materials strewn across the ocean floor, announced today that it has applied for a permit from the Trump administration to start commercially mining in international waters. Together, the company and President Trump are circumventing a multilateral process to develop rules for deep sea […]

The Metals Company, which has been trying for years to exploit battery materials strewn across the ocean floor, announced today that it has applied for a permit from the Trump administration to start commercially mining in international waters.

Together, the company and President Trump are circumventing a multilateral process to develop rules for deep sea mining that has so far prevented any commercial exploitation from happening.

Moving forward with mining now, before fully understanding the potential environmental impact or having international rules in place to mitigate the damage, is already angering other governments and conservation groups.

“An act of total disregard for international law”

“The first application to commercially mine the seabed will be remembered as an act of total disregard for international law and scientific consensus,” Greenpeace International senior campaigner Louisa Casson said in a press release. “Governments around the world must now step up to defend international rules and cooperation against rogue deep sea mining.”

Trump signed an executive order last week to try to fast-track deep seabed mining, which he framed as a way to counter China’s dominance in mineral supply chains. The Trump administration claims it has authority to grant permits to mine through the 1980 US Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act and because the US has not ratified the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The Convention, ratified by more than 160 other nations, established the International Seabed Authority (ISA) that is in the process of crafting rules for deep sea mining.

Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Guo Jiakun said the executive order “violates international law and harms the overall interests of the international community,” the BBC reported on Friday.

The island nation of Nauru initially sponsored The Metals Company (TMC) and its deep-sea mining effort, setting off a scramble to develop international regulations in 2021. The ISA missed a 2023 deadline to draft those rules after failing to reach consensus on thorny issues like who’s liable for paying for any damage that might occur. Scientists and environmental advocates have also argued that there’s still too little we know about the ocean’s abyss to fully understand the risks, let alone mine responsibly there.

The surface of the Moon is better mapped than the world’s seafloor, where scientists are still making surprising discoveries that raise questions about whether mining there could have far-reaching effects on marine life and coastal communities. More than 30 countries — including US neighbors Canada and Mexico — have called for a ban or moratorium on deep-sea mining until there are international rules in place.

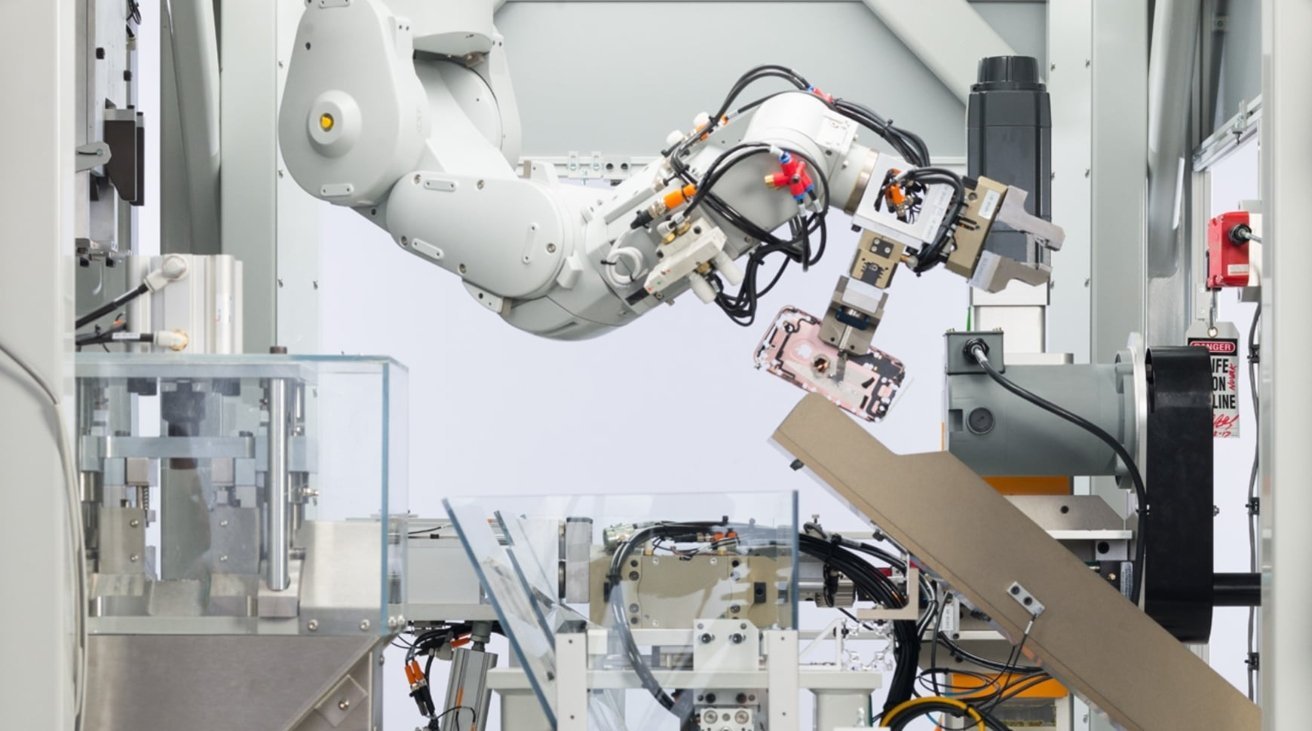

TMC, apparently, is tired of waiting. It has applied for a permit from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to harvest materials from a 25,160 square kilometer-swath of seafloor roughly 1,300 nautical miles south of San Diego. It also applied for two licenses to explore more areas for mining potential. The permit is for an area that’s part of the Clarion Clipperton Zone, a region between Hawaii and Mexico that lies outside of US national jurisdiction and where mining is supposed to be regulated by the ISA, NOAA has previously said on its website. The Clarion Clipperton Zone is full of life that scientists have recently discovered; up to 90 percent of species collected for study here have been completely new to science.

The zone has also been a focus of proposed deep sea mining efforts because the seafloor is covered in rock-like polymetallic nodules full of nickel, cobalt, and manganese used in rechargeable batteries and deemed “critical minerals” by the US government. Trump has made sweeping threats in the name of securing critical minerals, from annexing Greenland to warning Ukraine of “big, big problems” if it backed out of a critical minerals deal.

Trump is reportedly fond of the nodules. “I’m happy to say, a nodule just like this one was presented to the president last week and now sits on the resolute desk,” Gerard Barron, chairman and CEO of The Metals Company, said during a House Natural Resources Committee oversight hearing held today.

“We are offering the United States a shovel-ready path to new and abundant supplies of nickel, copper, cobalt, and manganese—critical metals for energy, infrastructure, and defense,” Barron said in a press statement announcing the permit application. “After continuous delay at the international level, the United States now has a clear opportunity to reclaim its leadership role in the deep sea.”

The Metals Company says it has invested more than half a billion dollars “preparing for this moment,” and believes it can recover up to 15.5 million metric tons of nickel, 12.8 million metric tons of copper, 2 million metric tons of cobalt, and 345 million metric tons of manganese from the Clarion Clipperton Zone. TMC also contends that mining at sea would be less harmful than mining on land and has repudiated a controversial study published last year — which the company had initially funded — that found evidence of mysterious “dark oxygen” rising from the deep sea.

Opponents of deep sea mining, meanwhile, point to alternatives that limit the need to pluck nodules from the seafloor. EV companies, including Tesla, have worked towards reducing the use of nickel and cobalt in batteries. And it’s been estimated that by 2050, half of cobalt and nickel demand for EVs in the US could be met through recycling.